Types of Nouns

The following is slightly complicated, so I will try to explain it slowly.

Previously, we have examined how adjectives change in gender, case, and number. Adjectives don't have their own gender, case, or number — instead, you can (and must) create any combination of these for any adjective when needed.

Now, there's another issue: you must also change nouns, first to make plural ("boy"-"boys") but then also to make various case forms that correspond to roles in a sentence (sorry, no English equivalent). Unfortunately, there are various schemes to do that, called 'declension types', or just 'types'. In principle, they don't need to be connected in any way to the gender of a noun. In the modern Croatian, there is however a close connection between noun types and noun gender, but they are not really identical.

If you would like something in English you can compare this with, consider gender and patterns of noun plural:

m f n strong man-men woman-women tooth-teeth weak boy-boys ship-ships ball-balls

It's not really the same, but it's similar in a way: there are two 'declension classes' (ways to make plural) in English and three genders. They are completely independent in English, but in Croatian they are not. There's a similar situation in German: there are five ways to make plural and three genders, and they are not independent: nouns that have -(e)n in plural are mostly feminine, those that have -er are never feminine.

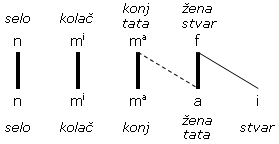

What I call e. g. 'a-noun' means how the noun changes. The basic 'types' are:

a-nouns: they all belong to the f gender, except for a very small number that belongs to mª gender (e.g. tata "Dad"); one recognizes them easily, since they end on -a in nom.sg. (hence their name).

m-nouns: they are divided further to mª and mi subclasses; they host only nouns with genders mª and mi (but not all of them, a few mª-nouns are in the a-class); they mostly end on a consonant in nom.sg.

n-nouns include all nouns of n gender, and only them; they end on -o or -e in nom.sg.

i-nouns include a not so small number of nouns (around 250 and more, you'll see my point later), all having f gender; they end on a consonant in nom.sg. (except for a few). You need to learn their list by heart. You can postpone learning them and return to them later, of course. Some examples are noć "night", jesen "autumn, fall" etc.

Furthermore, there are some adjectives 'serving' as nouns. They have a case change pattern exactly as an adjective, but behave otherwise completely as nouns do — their gender is also fixed. They are mainly place names. The chief example is name of the country itself — Hrvatska "Croatia".

Irregular nouns are oddballs and don't fit in the 5 previous classes. You learn them the hard way, all forms by heart.

Warning: for many nouns it's straightforward to know their type and gender. But there are some exceptions, for instance, auto is an mi-noun, misäo "thought" an i-noun, and oräo "eagle" an mª-noun. Beware, there are some additional types, I will explain them later.

To summarize relations between gender and noun types:

Each noun belongs to a gender and to a noun type.

Gender tells you what form of adjectives or pronouns to use

with a noun; how adjectives and pronouns adapt ("agree") to the noun.

Noun type tells you how to make plural of a noun, how to create other

cases etc., that is, how the noun itself changes when in various roles.Noun types are also called 'declension types'.

(Declension = how a noun changes, what endings it gets)

In Croatian, gender and noun types largely overlap.

Some books oversimplify things: instead of introducing e.g. a-nouns simply use 'feminine nouns'. Then you have an awkward situation that tata "Dad" is a 'feminine' noun. But there's a major problem: with tata you must use masculine forms of adjectives (moj tata and not moja tata!) and that is hard to explain from that standpoint. In my point of view, separating how nouns change from what forms of adjectives must be used with them keeps the concepts clear.

This is probably confusing a lot. There's a simpler way to group nouns, into 6 groups, each corresponding to one line in the chart above. The only difference is a special status of a-nouns belonging to the mª gender (the combination I will indicate as a/mª-nouns):

group ending in nom.sg. gender n -o mlijëko "milk", selo "village" n -e more "sea", lice "face" mi cons. zrak "air", kolač "cake" mi (-o) auto "car", dio "part" * mª cons. päs "dog", sin "son" mª (-o) oräo "eagle", Marko (name) * a/mª -a tata "dad", Luka (name) (-o, -e) Ivo (name), Ante (name) * a -a voda "water", riba "fish" f i cons. sol "salt", krv "blood" *

Only a small number of nouns have endings in parentheses (..): you can consider them exceptions. Bear in mind, this table does not show all exceptions out there. Gender and declension type of all nouns in groups and subgroups indicated by an asterisk (*) cannot be guessed and must be learned.

Also, for now, you could consider all the i-nouns and a-nouns that are not of the f gender (e.g. tata "Dad") as exceptions. There is only a limited number of such nouns, after all. For most nouns it's easy to guess their gender from their nom.sg. (i.e. dictionary) form, just by looking at their last sound:

For the majority of nouns,

their gender can be guessed from their ending in nom.sg.:

- nouns ending on a consonant are mostly masculine (animate or inanimate)

- nouns ending on an -a are mostly feminine (a-nouns)

- nouns ending on an -o or -e are mostly neuter (n-nouns)

Normally, it's not needed to remember the noun type and gender for 95% of nouns or more. For instance, when you see voda "water", you will assume that it's an a-noun (since it ends on -a), and feminine (as almost all a-nouns are), and you'll be completely right! So you see, actually it's simpler than it looks at the first sight... Therefore, it's worth marking gender of nouns only if it does not follow this approximate rule.

There's no need to mark gender of voda "water" or kuća "house". However, the noun jesen "autumn" has not the mi gender, but unexpectedly the f gender (it's an i-noun), therefore it must be marked: jesen f "autumn". Likewise, jezero "lake" is neuter as expected, but auto mi "car", misäo f "thought" and posäo mi "job" are not. On the other hand, prijatelj "(male) friend" is a mª-noun, as expected, and therefore I don't need to indicate its gender.

I'll indicate only things that are not 'default'.

Let's take a look at the case forms for the following nouns:

- n-nouns selo "village" and more "sea"

- a-nouns žena "woman, wife" and ruka "hand, arm"

- i-noun stvar f "thing" (remember, all i-nouns are feminine!)

We'll postpone m-nouns for the next chapter/entry since they are a bit more complex than the other three types. There's no need to list forms of adjectives serving as nouns — they have forms exactly as adjectives have.

case n-nouns a-nouns i-nouns nom.sg. selo more žena ruka stvar acc.sg. ženu ruku dat.sg. selu moru ženi ruci stvari nom.pl. sela mora žene ruke stvari acc.pl. dat.pl. selima morima ženama rukama stvarima

Some a-nouns ending on -ka (e.g. ruka) change that k in dat.sg. to c. However, that does not happen for all a-nouns ending on -ka, so I will indicate when dat.sg. has -ci instead of ki. The similar thing happens for some nouns ending on -ga (e.g. noga "leg, foot") that have -zi instead of gi in dat.sg.

You see now why i-nouns are called so: they always have an -i- in their endings (except in nom.sg.). Some people call them 'feminine nouns ending on a consonant'. That's also right, but a bit less precise.

The Pattern

Since only endings change, we can list endings only, and take into account that a lot of these endings are the same: both more and selo have the same endings, except in nom.sg. It's quite similar to declension (forms of cases) of adjectives, but the endings are not the same, except for some cases.

I hope you can see that the pattern is not as complicated as it could be: many cases actually share endings, especially in plural.

I'll indicate the possible change k → c or g → z with a + in the scheme. Here's the scheme of endings only:

case n-nouns a-nouns i-nouns nom.sg. -o, -e -a - acc.sg. -u dat.sg. -u (+)i -i nom.pl. -a -e -i acc.pl. dat.pl. -ima -ama -ima

I know it's not easy at all to remember endings, especially in singular. Maybe it would be best to remember whole 'template phrases' — nouns and adjectives — so you learn what forms go together. Here I will list only 'typical' words, forgetting for a moment there are a-nouns that are not of f gender, etc. I shaded cases where adjectives and nouns ave different endings.

no. nouns nom. acc. dat. sg. n- veliko selo

veliko morevelikom(u,e) selu

velikom(u,e) morua- velika kuća veliku kuću velikoj kući i- velika stvar veliku stvar velikoj stvari pl. n- velika sela

velika moravelikim selima

velikim morimaa- velike kuće velikim kućama i- velike stvari velikim stvarima

This is maybe too much to learn at once; you could try the following approach:

- Try to learn a-nouns and adjectives in feminine first.

- Then check neuter gender and nouns and corresponding adjective forms. They are quite similar.

- Once you learn them, move to the i-nouns — you don't need to learn more adjective forms, you have already learned adjectives in feminine gender.

Nominative vs. Accusative

One curiosity: there's much less difference between nom. and acc. (check plural forms) that one would expect from Croatian. For instance, since both žena "woman" and knjiga "book" are ordinary a-nouns, the sentence "women are reading books" is somewhat ambiguous! There's no difference between nom.pl. and acc.pl.; so, when it's translated to Croatian, it might actually mean "books are reading women":

Žene čitaju knjige.

Knjige čitaju žene. (who is reading?)

Then the word order kicks in, as in English. And the common sense.

Vocabulary

Here are some common a-nouns; all nouns in the list are feminine, except for tata "Dad" (it's therefore marked as mª):

banka "bank"

cijëna "price"

cipela "shoe"

crkva "church"

čaša "glass (to drink from)"

glava "head"

juha "soup"

haljina "dress" (women wear)

hrana "food"

kava "coffee"

kiša "rain"

kosa "hair" (on a head)

košulja "shirt"

kuća "house"

lubenica "watermelon"

majica "T-shirt"

mama "mom"

naranča "orange"

obala "shore"

pjësma "song"

plaža "beach"

pošta "post office, mail"

ptica "bird"

razglednica "picture postcard"

riba "fish"

riža "rice"

sestra "sister"

soba "room"

stolica "chair"

škola "school"

tata mª "dad"

trava "grass"

večera "supper"

vilica "fork"

voda "water"

zemlja "ground, earth"

žena "woman, wife"

zgrada "building"

žlica "spoon"

Common a-nouns that end on -ka or -gi, with their dat.sg. forms listed in parentheses (...) are:

baka (baki) "grandmother", "old woman"

jabuka (jabuci) "apple"

knjiga (knjizi) "book"

luka (luci) "harbor"

mačka (mački) "cat"

majka (majci) "mother"

marka (marki) "postal stamp"

noga (nozi) "leg, foot"

patka (patki) "duck"

ruka (ruci) "arm, hand "

You can maybe see an approximate rule: if such nouns have another consonant right before k, there's no change (e.g. patka → patki).

There are few common male names that belong to a-nouns, more precisely to the a/mª group:

Andrija mª

Borna mª

Ilija mª

Luka mª

Matija mª

Nikola mª

Saša mª

Siniša mª

(Actually, there are more male names that belong to this group, but — exceptionally — they don't end on -a in nom.sg.! Such names are covered in 45 Nouns for Small and Dear.)

Common n-nouns (all neuter!) are:

drvo "tree, wood"

jaje "egg"

jelo "dish, meal"

jezero "lake"

jutro "morning"

lice "face"

meso "meat"

mjësto "place"

more "sea"

piće "drink"

pismo "letter"

pivo "beer"

povrće "vegetable(s)" *

selo "village"

smeće "trash"

stäklo "glass (of a window)"

sunce "sun"

tijëlo "body (of a person)"

vino "wine"

voće "fruit(s)" *

Nouns povrće and voće can represent any quantity of fruit and vegetables, they are similar to meso "meat" and smeće "trash".

Common i-nouns (once more, they are all feminine!) are:

bol "pain"

bolest "disease"

jesen "autumn, fall"

kost "bone"

krv "blood"

mast "fat, ointment"

noć "night"

obitelj "family"

ponoć "midnight"

rijëč "word"

sol "salt"

večer "evening"

For an exhaustive list of i-nouns, check 89 Abstract and I-nouns.

Exercise

JavaScript must be enabled. You don't have to use my special notation (e.g. ë) in answers, normal spelling will do as well; letter case does not matter.

All above words are in the 'dictionary form' — nom.sg. Try putting these words in various cases, and making sentences as:

Imam __________. "I have (a)..." (insert a noun in acc.)

Trëbamo __________. "We need (a)..." (insert a noun in acc.)

Jedem __________. "I'm eating..." (insert a noun in acc.)

Pijemo __________. "We're drinking..." (insert a noun in acc.)

Molim __________. "I would like (a)..." (insert a noun in acc.)

Idem u __________. "I'm going to (a/the)..." (insert a noun in acc.)

Ja säm u __________. "I'm in (a/the)..." (insert a noun in dat.)

Be careful with a-nouns ending on -ka...

Updated 2014-11-03 (v. 0.4)

10 comments:

They have seen a wolf, in croatian should be: oni su vidjeli vuk. noun vuk is in accusative, right? but I've seen sentence with vuka, not vuk. oni su vidjeli vuka.

is this irregular or what?

OK, my bad. I'm making a fine progress with my croatian thanks (among others) to your page. still, not a easy language to learn. Thanks a lot for your work.

Why insert a noun in dat ? Ja sam u __________. "I'm in (a/the)..."

Because after u "in" there should be a noun in dative/locative if it stands for "location".

Why? It's just so, historic reasons. We say ja sam u sobi "I'm in the room".

If you think it should be locative, and not dative -- well they are the same, at least they are spelled in the same way, so it was a simplification.

br Daniel

volim te do neba in english i love you to the skies

in this sentence why is using neba?

in my thought,

nebo is a neuter singular

and in the sentence nebo is a nuter plural in dat. case

so,i think nebo should be changed to neboima

but why nebo change to neba?

No, nebo is neuter singular, and neba is genitive sg. There's only one "sky" in Croatian, the sky. There's no "skies" (well there are in some expressions) since there's only one sky, only one Earth etc. You cannot just translate phrases literally...

Next, the preposition do uses genitive as explained here:

Basic Prepositions and Government

In fact, most prepositions require genitive. Only couple of them require dative, accusative or instrumental.

br Daniel

Zemljovid na vašem blogu pokazuje, to jest promiće nepostojeći jezik. Uza hrvatski jezik potrebno je postaviti i zemljovid koji prikazuje područje koje obuhvaća hrvatski jezik.

Slažem se da je postojeća karta (zemljovid je knjiška riječ koju malo tko koristi) zbunjujuća pa sam je uklonio. Ne postoje dobre karte koje prikazuju područje hrvatskog jezika jer je hrvatski jezik tek apstrakcija i nemoguće ga je odvojiti od recimo bosanskog/bošnjačkog po ikakvim razumnim kriterijima.

Svakako postoji standardni hrvatski jezik, ali on se zapravo dosta malo govori (recimo, ja ga ne govorim).

Ovaj blog se ionako više ne održava, sve nove promjene su na easy-croatian.com

NB uobičajeni je pravopis "promiče" (od "promicati").

lp

Hello!

I'd be grateful if you could explain this to me.

I have read somewhere sljedeće godine translated as next year. But i am confused, doesn't it mean next years? Like plural?

For singular, wouldn't it be sljedeća godina?

Thank you

It's genitive singular. And nominative plural. But nominative is not used for time periods. Please read easy-croatian.com, as this is no longer maintained.

Post a Comment